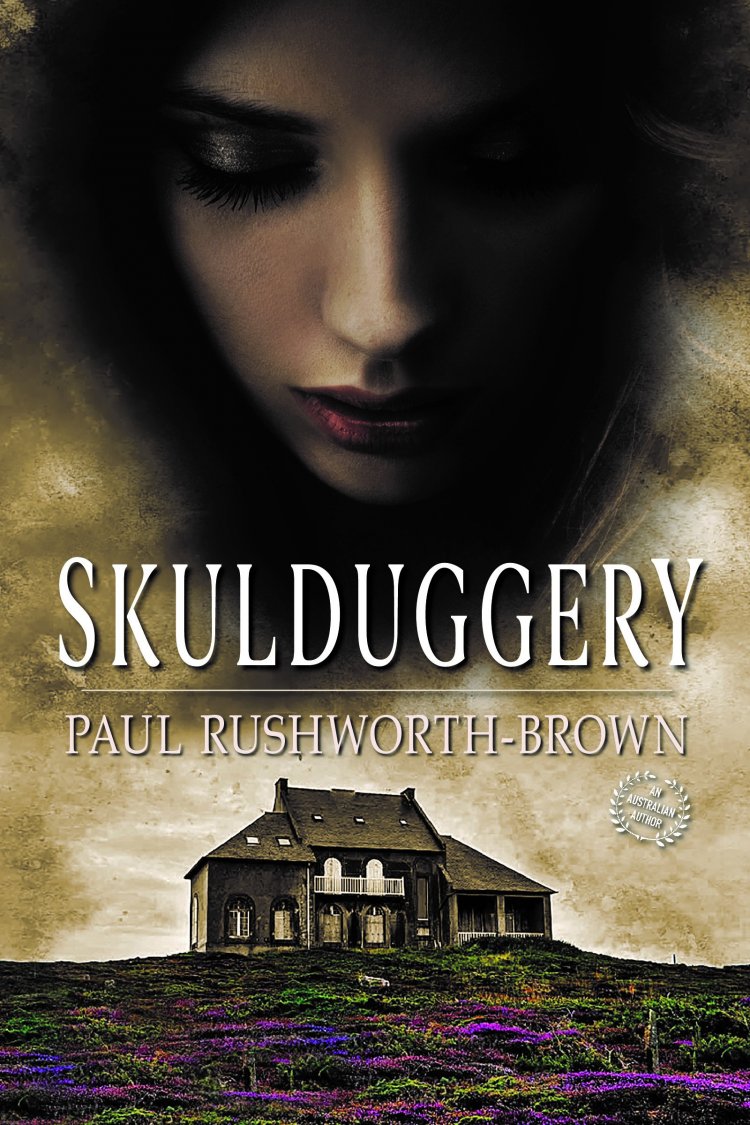

Launching a new book: Skulduggery

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES: The word ‘gong’ is derived from the old English, gang, which means ‘to go’ and seems to have been used to describe a privy or latrine in the early 11th century.

The ‘gong farmer’ was someone who dug out and removed human excrement from privies and cesspits in 14th to 17th century England. Gong farmers were only allowed to work between 9 pm and 5 am as members of the public did not want to see them at work digging and collecting the ‘night soil’.

Night soil is a historically used euphemism for human excreta collected from cesspools, privies, pail closets, pit latrines, privy middens, septic tanks, etc. This material was removed from the immediate area and often transported out of towns and sold on as a fertilizer. The modern term is faecal sludge.

Cesspits were made from brick chambers about six feet deep and four feet wide. They were placed as far away from the house as possible, but sometimes they were installed in the basement and were often placed under cellar floors or in the yard of a house. Some had wooden chutes to carry excrement from the upper floors to the cesspit, sometimes flushed by rainwater. Cesspits were not watertight, allowing the liquid waste to drain away leaving only the solids to be collected. After being dug out, the solid waste was removed in large barrels, which were loaded onto a horse-drawn cart.

A foul odour from cesspits was a continual problem, and the accumulation of solid waste meant that they had to be cleaned out every two years or so. In the late 15th century, they charged two shillings per ton of waste removed.

The working life of a gong farmer was spent up to his knees, waist, even neck in human excrement. It was also an extremely dangerous job, as gong farmers often dug into pockets of deadly poisonous gas and of course risked disease. Sometimes the gong farmer would be overcome by asphyxiation from the noxious fumes produced by the human excrement.

A gang of four men (exclusive of those who have the care of the horses, and who drove the night-carts to and from the scenes of the men’s labours at the cesspools) were set to work. The labour of the gang was divided, though not with any individual or especial strictness, as follows: The holeman, who went into the cesspool and filled the tub, the ropeman, who raised the tub when filled and the tub men (of whom there are two), who carried away the tub when raised and emptied it into the cart.

From this, we can see that much of the work was done from a surface level, and though lanterns were used, it was not necessary to enter the dangerous areas with the lanterns due to the build-up of methane gas. The lanterns were placed nearby or suspended over the work area.

Much of what is known about privies during the 17th and 18th centuries comes from witness statements describing what had been discovered among the human excrement, such as the corpses of unwanted infants.

From the early 17th century onwards the larger towns and cities began to employ scavengers, as they became known, to remove waste from the streets. Much of this effluent came from overflowing privies and dunghills, or from chamber pots emptied into the streets from upstairs windows.

Paul Rushworth-Brown is the author of three novels available in paperback, ebook or KOBO.