Study: Unique treatment attacks blood clots without raising blood risk

Washington, US: A new finding by researchers at UBC and the University of Michigan, published today in Nature Communications, might lead to safer and more effective blood thinners.

The researchers created a new substance called MPI 8 by combining their expertise in blood clotting systems and chemical synthesis. It has the potential to prevent blood clots without increasing the risk of bleeding, which is a major side effect of existing blood thinners.

"The development of MPI 8 represents a major breakthrough in the field of blood clot prevention and treatment," said Dr Jay Kizhakkedathu, professor and Canada Research Chair at UBC's pathology and laboratory medicine department and the UBC Centre for Blood Research. "By targeting a specific molecule involved in clot formation without disrupting the natural clotting process, we've created a blood thinner that has proven safer and more effective in animal models, with enormous potential to improve human lives as well."

Further research will be needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of MPI 8 in humans, but initial results offer hope for a new era in blood clot prevention and thrombosis treatment while serving as a testament to the power of collaboration in research medicine.

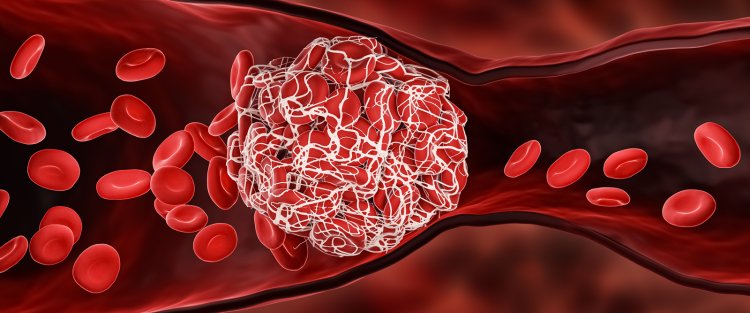

Blood clots are a serious health concern affecting millions of people around the world. Left untreated, they can lead to life-threatening conditions such as deep vein thrombosis, heart attack, pulmonary embolism and stroke.

Blood thinners, also known as anticoagulants or antithrombotic drugs, are essential in the treatment and prevention of blood clots but carry a significant risk of bleeding. This can cause complications and limit their use in some patients.

Existing blood thinners such as heparin, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and warfarin work by targeting enzymes that are essential for blood clotting. However, they must be carefully dosed and monitored because disabling those enzymes threatens the normal clotting process required to heal wounds.

UBC and Michigan researchers took an innovative approach to target instead polyphosphate, a molecule involved in blood clotting that accelerates the process but is not essential for it.

"Our thought was that polyphosphate might be a safer target to go after with an antithrombotic drug because it would just slow these clotting reactions down--even if we take out 100 per cent of the action of the polyphosphate," said Dr. Jim Morrissey, a professor of biological chemistry and internal medicine at the University of Michigan whose work has illuminated the role of polyphosphate in blood clotting. "We really had to come up with an extremely novel way to target it compared to the usual drugs that target clotting, and that's where the expertise of Dr. Kizhakkedathu's lab became so important."

After building a library of potential molecules and screening them for their desired criteria, the Kizhakkedathu lab zeroed in on MPI 8. This unique molecule has "smart" binding groups with positive charges that are drawn to polyphosphate's negative charge. It will bind to polyphosphate and inhibit it while leaving the body's other negatively charged cells and proteins alone, eliminating toxic side effects.

In preclinical studies, MPI 8 demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in preventing blood clots in mice without increasing bleeding risk. The drug showed no signs of toxicity, even at high doses.

"Not only does the drug show promise as a safer and more effective option for patients, but the design platform we used to create MPI 8 is flexible, potentially allowing for the development of additional compounds with similar properties and efficacy," said Dr. Chanel La, who worked on the project as a chemistry PhD student in the Kizhakkedathu lab. "Assuming our work continues to produce positive results, I would be very excited to get MPI 8 into an approved clinical trial and bring this drug closer to becoming a reality for needy patients."

UBC and the University of Michigan have filed a patent application for the technology.