Why everyone - man or woman- needs to read the unknown author Elena Ferrante

A daring tale about the many complications of a woman and her life, Ferrante has a little bit of something for both men and women alike.

No one knows who the real woman is behind the pseudonym, Elena Ferrante, and yet when she speaks of Naples trapped in the conservative ideals of the early ‘50s and later on the glaring ‘70s, you cannot help but recognize her in the narrator of the story, Elena Greco (Lenu). A seemingly calm-headed girl who in her attempt to find her place in the world follows around her friend, Raffaella Cerullo (Lila). The gritting tale about friendship which can be as complex as any other relationship and yet is the only relieving factor in a society constantly trying to mend itself from the remains of a war, Ferrante’s novel is a glaring reality of the contemporary era through the windows of a long gone decade.

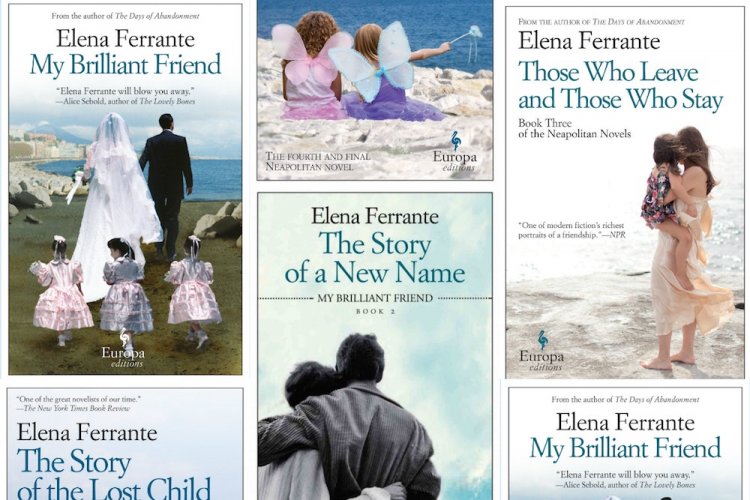

In her four-part Neapolitan Series, Ferrante dives into the complex friendship between two friends and puts its loyalty to test when that friendship is bound to endure the changing needs of society and personal desire. The first part, ‘My Brilliant Friend’, which found a mesmerizing on-screen rendition on HBO under creator Saverio Costanzo, introduces us to the dilapidating post-World War Naples which is trying to recover from its poverty. The narrator Lenu walks us through the poverty-stricken neighbourhood where she grows up with her best friend, Lila, witnessing violence both without and within her family. The first novel itself picks up a paradoxical tone where on one hand the story is being told by a 60-year-old woman from the perspective of a child, and on the other hand it reflects the fears of a 10-year-old child in a post-war Naples.

The first book was brilliantly adapted by HBO. (IMDb)

It is perhaps this paradoxical tone which entrusts the child-like innocence of a newly freed country against the looming evil of a war which has left behind its many dilapidated morsels. Growing up Lila and Lenu, play with ragged dolls, wear the same tattered clothes every day, and are constantly subjected to the brutality of a post-war generation who had only a decade back found themselves in the trenches of war. Amid all the harshness that society had to offer, the two children find joy in Louis May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’, and even here Ferrante gives a striking distinction in the nature of perseverance of the two friends. While Lenu reads the book cover to cover with Lila, she enjoys every bit of it so much that the four March sisters begin to grow within her. On the other hand, Lenu who equally enjoys reading the book, finds out the monetary qualification and decides to write books as a mean to earn money. This tiny moment of interaction between the two friends gives us two distinct images of the post-war generation- one image being of those who want to see life as it is with all the joy and the pain equally measured, the other image of those who desperately want to move far away from the ruination left behind by the preceding generation.

The two friends grow up reading ‘Little Women’ cover to cover. (Google)

The next two books in the series, ‘The Story of a New Name’ and ‘Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay’, watch the girls march bravely into their adulthood. Although their experiences begin to shape them as very distinct personas, their tendency to hold on to each other strengthens with every passing moment. Newly married to the son of a local businessman, Lila faces her greatest fear when she is raped by her husband on the night of their marriage. However, she manages to remain as sturdy as she has always been and soon takes on her father’s shoe business. Lila’s transformation from a girl who was merely angry and hid herself from society to a woman who almost struck a deal with society for a better livelihood once again is seen through the mirror of Lenu’s narrative. Lenu, herself now a published author, embarks upon a complicated yet seemingly satiating journey as a writer where she comes in contact with Communist parties, fellow authors, and goes back to her childhood friends each of who are fighting a war of their own. More subtle yet impregnable in their tone, the two books watch the two women curve out their own spaces in the social structure which now fiercely racing towards a modern era.

It is not until the final book, ‘The Story of the Lost Child’, that we actually witness Ferrante’s fuming frustration. Grown up with children of their own, Lila and Lenu’s friendship is once again put to test- only this time not by society but by their own vehement morales. Once again Ferrante’s novel takes a child’s perspective but that serves a secondary purpose here since the narrator is not the child herself, although she is constantly looking at the world around her through the varying views of her own children and her best friend’s brilliant daughter. As one last stroke of loss and pain, Lila continues to remain suppressed by her own insecurity and yet the novel juggles between selfish victory and selfless pain, when looking into the tormenting life of these two women.

Although Ferrante’s Neapolitan series chiefly deals with the many facets and complications of the friendship between two women, it equally picks up on some basic yet significant themes such toxic masculinity, brutality of parenthood, love and heartbreak, and finally the ever paradoxical social structure that alters with time but remains grounded in its flaws. What perhaps makes the Neapolitan series an even compelling read is its tendency to reside on the no-man’s land between fiction and non-fiction. Compared to Norwegian author, Karl Ove Knausgaard, who's ‘My Struggle’ series is immersed in reality, Ferrante’s work does not take the highroad to realism. Instead it touches upon the realistic facets of life, with an autobiographical tone, but maintains the nature of a fiction that rises from the imagination of someone who takes life for the way it is served.

Knausgaard had taken a more personal approach as compared to Ferrante. (Google)

The Neapolitan series is perhaps the final installment in Ferrante’s lifelong journey of exploring the many phases in a woman’s life. We already get hints of a broken marriage in her 2002 novel ‘The Days of Abandonment’ and the hurling grief of losing a child in her 2006 novel, ‘The Lost Daughter’. Ferrante is that rare gem of a writer that most of us fail to recognize today. Her approach is feministic but her conclusion continues to remain humane. She isn’t somebody writing solely to empower a woman over a man, but she is someone who dwells upon the marginal idea about women not being subordinate or higher sex than men, but are equally brilliant and equally sinful in their own manner.