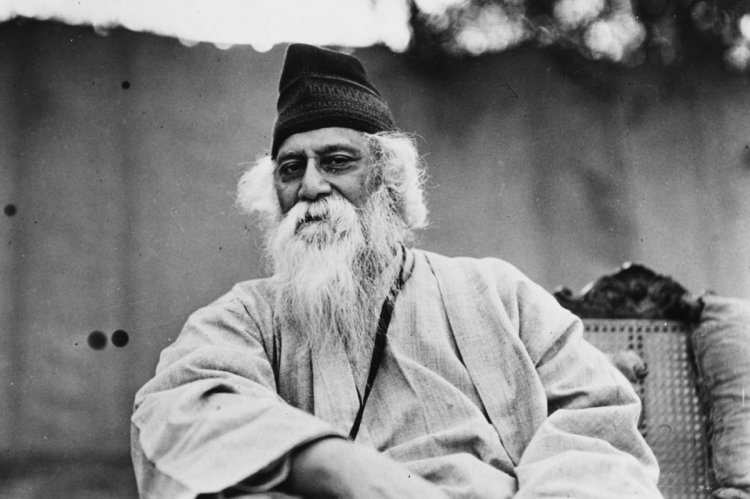

Rabindranath Tagore: The Illimitable Noble Laureate

There is no one way to describe the great poet, Rabindranath Tagore. He was a Bengali poet, writer, song composer, playwright, essayist and painter from the Indian subcontinent. Rabīndranāth Ṭhākur, (born May 7, 1861, Calcutta [now Kolkata], India- died August 7, 1941, Calcutta) introduced new prose and verse forms and the use of colloquial language into Bengali literature, thereby freeing it from traditional models based on classical Sanskrit.

He was highly influential in introducing Indian culture to the West and vice versa, and he is generally regarded as the outstanding creative artist of early 20th-century India. In 1913 he became the first non-European to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

He reshaped Bengali literature and music, as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Most of his finest short stories, which examine “humble lives and their small miseries,” date from the 1890s and have poignancy, laced with gentle irony that is unique to him (though admirably captured by the director Satyajit Ray in later film adaptations). Tagore came to love the Bengali countryside, most of all the Padma River, an often-repeated image in his verse. During these years he published several poetry collections, notably Sonar Tari (1894; The Golden Boat), and plays, notably Chitrangada (1892; Chitra). Tagore’s poems are virtually untranslatable, as are his more than 2,000 songs, which achieved considerable popularity among all classes of Bengali society.

His first notable book of lyrics, Sandhya Sangit (1882; “Evening Songs”), won the admiration of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Tagore later wrote in his Reminiscences, “the sadness and pain which sought expression in the Evening Songs had their roots in the depth of my being.” The book was closely followed by Prabhat Sangit (1883; “Morning Songs”), in which he celebrated his joy at the discovery of the world around him. The new mood was the outcome of a mystical experience he had had while looking at the sunrise one day:

“As I continued to gaze, all of a sudden a covering seemed to fall away from my eyes, and I found the world bathed in a wonderful radiance, with waves of beauty and joy swelling on every side. This radiance pierced in a moment through the folds of sadness and despondency which had accumulated over my heart, and flooded it with this universal light,” he recalled.

Tagore progressively started producing an assortment of imageries including imaginary and distinctive creatures, facemasks, mystical human being faces, mystical sceneries, flora and fauna. Crossed-out lines and words would take unplanned and accidental shapes, driven by spontaneous decisions, usually growing from the memories of art and the objects he saw in museums and books, along with his various visits to countries abroad.

As a little boy growing up in the lap of nature, he often spent time enchanted in all that nature had to offer to man. It was an introspection of the larger relationship that man nurtured with the all-giving Mother Nature and her labyrinth that he lived in. He described the visible world around him ‘as a vast procession of forms.’ He spent hours observing the forms of nature from his window, often forming dialogues that formed the articulations of his poetry and literature as well as visuals to his drawings and paintings.

Tagore’s novels in Bengali are less well known than his poems and short stories; they include Gora (1910) and Ghare-Baire (1916), translated into English as Gora and The Home and the World, respectively. In the late 1920s, when he was in his 60s, Tagore took up painting and produced works that won him a place among India’s foremost contemporary artists.

Tagore’s three main sources of his literary inspiration were: the Vaishnava poets of medieval Bengal and the Bengali folk literature; the classical Indian aesthetic, cultural, and philosophical heritage; and the modern European literary tradition, particularly the work of the English Romantic poets. Underlining Tagore’s many affinities with the European mind, Alexander Aronson, in Rabindranath through Western Eyes, tried to fit him into the Western literary tradition, but, as Edward J. Thompson pointed out in Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Dramatist, “Indian influences, of course, were the deepest and touched his mind far more constantly than any European ones, and at a thousand points.”

A substantial amount of Tagore’s writing was in the form of nonfictional prose—essays and articles, religious and philosophical treatises, journals and memoirs, lectures and discourses, history and polemics, letters, and travel accounts. Of these, his philosophical writings- Sadhana: The Realisation of Life (1913), Nationalism (1917), Personality (1917), Creative Unity (1922), The Religion of Man (1931), and Towards Universal Man (1961) were central to his thought. These writings were deeply influenced by the teachings of the Upanishads.

In the preface to Sadhana, which was published in the Harvard lecture series, he confessed, “The writer has been brought up in a family where texts of the Upanishads are used in daily worship; and he has had before him the example of his father who lived his long life in the closest communion with God while not neglecting his duties to the world or allowing his keen interest in all human affairs to suffer any abatement.”

A Modernist

Tagore consistently spoke out against all forms of xenophobia, assertions of ethnic superiority, or chest thumping nationalism.

In a 1908 response to a question whether he was a patriotic Indian, Tagore noted:

“Patriotism cannot be our final spiritual shelter; my refuge is humanity. I will not buy glass for the price of diamonds, and I will never allow patriotism to triumph over humanity as long as I live.”

A similar clarity coursed through Tagore’s writings about religion. Although deeply spiritual, he consistently denounced all forms of religious intolerance and exclusivity.

Tagore’s biography encompasses other noteworthy aspects as well. In the field of education, he led the drive to create a school that ultimately evolved into the world-renowned Visva Bharati University. Its famous alumni include, among others, the Nobel Prize economist Amartya Sen, India’s Prime Minister Indra Gandhi, Oscar-winning film-maker Satyajit Ray, and prominent contemporary artists such as K. G. Subramanyan and Mithu Sen.

At this school, Tagore advocated against rote learning and for the importance of a vocational education- principles that modern educationalists agree are central to effective learning.

Tagore is undisputedly a modernist, one who in distinct ways helped the nascent Indian Art Scene, understand its vocation in times where the country was itself reeling under its ambitions of development. His art was also a fresh and distinct rupture from his peers in Bengal who were creating largely political works, detailing the plight of the country and surviving in the post-Bengal famine phase. He said:

“Each of the hundreds of drawings and paintings is a living and balanced artistic organism that traces the extraordinary journey of a great man”.

Shanti Niketan

In 1901, Tagore founded an experimental school in rural West Bengal at Shantiniketan (“Abode of Peace”), where he sought to blend the best in the Indian and Western traditions. He settled permanently at the school, which became Visva-Bharati University in 1921.

Years of sadness arising from the deaths of his wife and two children between 1902 and 1907 are reflected in his later poetry, which was introduced to the West in Gitanjali (Song Offerings) (1912). This book, containing Tagore’s English prose translations of religious poems from several of his Bengali verse collections, including Gitanjali (1910), was hailed by W.B. Yeats and André Gide and won him the Nobel Prize in 1913.

Tagore was awarded a knighthood in 1915, but he repudiated it in 1919 as a protest against the Amritsar (Jallianwalla Bagh) Massacre.

He is a National Treasure, a gem to the society who imparted knowledge like no other and blessed are we to have an opportunity to divulge in his teachings.

Let us part now, with some excerpts from a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, written 120 years ago, titled “Deeno Daan”; which is very relevant in the contemporary religious and political scenario:

“There is no god in that temple”, said the Saint.

The King was enraged;

“No God? Oh Saint, aren’t you speaking like an atheist?

On that throne studded with priceless gems, beams the golden idol,

And yet, you proclaim that it is empty?”

“It is not empty; rather, it is full of royal pride.

You have bestowed yourself, oh King, not the God of this world”,

Remarked the saint.”