KC Sivasankar: The Hand Behind Legendary Cartoons of India

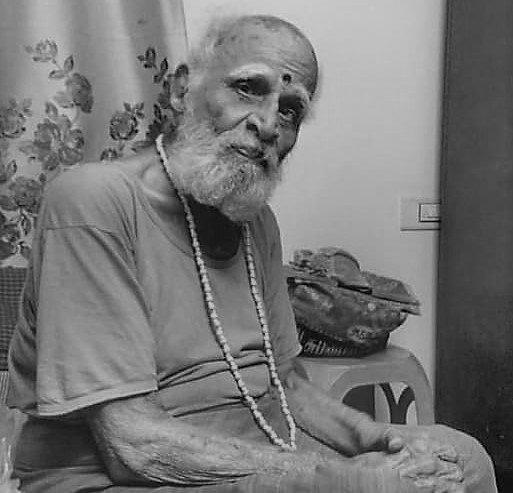

Sankar or KC Sivasankar who had contributed to for over five decades in creating cartoons, passed away on Tuesday due to age-related illnesses. He was 97.

He primarily contributed to the magazine, Chandamama (also known as Ambulimama). The magazine was published in 12 languages at one point. A close friend of his told that he passed away on Tuesday noon in his residence in Chennai.

Sankar is the artist behind the signature painting of the Vikram and Vetala series, showing the sword-wielding King Vikram carrying the corpse on his shoulder through a cremation ground - which is often synonymously remembered with the stories.

Sankar created the theme illustration for the King Vikram and Vetala series sometime in the 1960s. He worked for the magazine for 60 years and then joined Ramakrishna Vijayam magazine.

KC Sivasankar, talking about Chandamama cartoons, says:

“I am sure we all have read the Chandamama series at least once. Perhaps not the millennials but it was a must-read series for parents and grandparents.”

The Chandamama or the Ambulimama magazine was one source, which helped kids (before the Internet and smartphones) to recreate a story in their minds. Drawings were colourful with vivid expressions; they created a world of magic for kids to escape into!

Artist Sankar or KC Sivasankar has been contributing to the field of art for over 50 years. He says “I was in Class 5 and my brother was admitted in Class 2. For some reason, he didn’t want to study in the school and went back to our village,” he shared trying hard to recollect his childhood days.”

In 1942, he started to explore art and recalls that his teacher advised him to join the Government Arts College and pursue a career in this field. He remembers even today that his first job as an artist was for a magazine, which was not too appealing for him then: “The first artwork I did was by looking at my textbooks and drawing the animals and birds from that. Initially, I used to only see and draw,” said the artist.

When he completed his course at the Government Art College in 1946, a senior had asked him to join the Kalai Magal magazine, where he worked for five years. As 1951 was nearing, he joined the Ambulimama magazine, which was then run by Nagi Reddy, who Sankar considered his family. “My journey with the Chandamama started there and continued for the next 60 years,” beamed Sankar. “Yes, it’s hard to find Chandamama's work, but I wouldn’t say its dead; people still talk about it.”

Whether Chandamama as an art form changed? He answers: “The art had no change in its form, but the people’s response kept changing. I have received a number of letters from my readers, appreciating me for my imagination and how I managed to bring life to a character that does not exist. I am very happy to share that Chandamama is the only magazine today that shot up to being published in 12 languages from three in a short period,” he smiled.

As the only living artist from the Chandamama team, he shares a little of what exactly is expected out of this art. “This form of art is tricky, as it expects the artist to know what he is working on. The characters may have a cultural connection or may be fictitious, but the artist is expected to have knowledge about it before he starts work on it.” To excel as an artist, Sankar’s advice is to give one’s heart and soul to the piece one is working on and be truthful to whatever one does. “Adhathan naan panen!” he said casually.

Sankar doesn't remember when exactly he created the theme illustration for the King Vikram and Vetala series: “Sometime in the Sixties, I think.” But many other memories are vivid. When you ask him for his story, he begins to narrate it like a folk tale with the eagerness of a child. He is easily the brand ambassador of the innocent era he depicts in his drawings.

Sankar, or K.C. Sivasankaran, was born in 1924 in a village near Erode. His father was a teacher in the local school. In 1934, when a close relative living in Madras died, Sankar along with his mother and siblings came to the city to stay with the bereaved family.

He says:

“My elder brother was already in Madras, studying in Pachaiyappa's College. My father had told my mother to put us in a corporation school so that we did not remain idle. Corporation schools did not charge any fee. So, she took me and my younger brother to the corporation school in Broadway. There, as a test, we were asked to write the sentence, George V is our King. I wrote it immediately. I had beautiful handwriting. I was admitted to the fifth standard and my brother to the third standard. Because of my handwriting, the teachers always made me write the daily proverb on the notice board — this went on till high school.”

It was at the Muthialpet High School, where Nagi Reddi had also studied, that the drawing teacher discovered Sankar's talent as an artist and often made him come on Sundays — together they would correct the sketches made by the other boys. “‘Look! I asked them to draw a cat but it looks like a rat. What if the inspector of schools comes tomorrow? We will get a black mark.' In return he would give me drawing books, pencils and erasers.”

“It was he who advised me, ‘Son, do not go for BA or MA. I know your value. You must join the arts school.'”

Gaining admission to the five-year course at the School of Arts meant completing a three-week assignment to the satisfaction of the teachers. For one of the assignments, Sankar found that the paintbrush was not cooperating with him, but the effect the obstinate brush produced on paper surprised the principal, the legendary D.P. Roy Chowdhury. “‘Where did you learn the pen-and-knife treatment?' he asked. I just kept quiet. It is best to keep quiet at such moments. He straightaway admitted me to the second year,” laughs Sankar.

Immediately after passing out, in 1946, he joined the Tamil magazine Kalaimagal on a monthly salary of Rs. 85. By 1952, he was earning Rs. 150, but that wasn't sufficient to support a large family, so he was also moonlighting for other magazines, making another Rs. 150. That year, Nagi Reddi hired him for Chandamama, on a salary of Rs. 350: on paper it was shown as Rs. 300 only because Chithra, the chief artist, was drawing Rs. 350.

Chithra and Sankar began as rivals but went on to become best friends until Chithra died of peptic ulcer in 1979. “Nagi Reddi used to say, ‘Chithra and Sankar are the two bullocks of Chandamama. Without either of them, the bullock cart can't reach the village,'” recalls Sankar. His two other contemporaries, Razi and Vapa, are also no more. Today, since the magazine has become larger in format, Sankar is often called upon to expand their illustrations — for example, drawing the waist-down portion of a king or a hermit whose torso was sketched by one of his late colleagues four or five decades ago.

Sankar lived a modest life; But he has heard stories that make him feel rich: his favourite being that of a young shepherd in Orissa, who preserved his hard-earned copy of Chandamama by rolling it up and inserting it into the hollow of a bamboo. “You know, his ambition in life was to be able to draw like Sankar and Chithra,” said Sankar, with the excitement of a child.

In 2007, 60 years after it was first published, the magazine was acquired by Geodesic, a Mumbai-based software services provider company, with an intent to digitise its content. In 2013, Chandamama stopped publishing when the parent company ran into financial troubles following which in 2017, a volunteer driven effort began to revive and preserve the magazine for future generations.

Condolences came pouring in following Sivasankar’s demise with many fondly recalling his contributions to the field of art.

The children and now the grown ups could never get over the nostalgia of these cartoons that dominated our childhood; which in anyway will be always evergreen!

Rest in Peace KC Sivasankar!