Cultural Appropriation: Is It Appropriate Though?

Cultural appropriation is the adoption of icons, rituals, aesthetic standards, and behaviour from one culture or subculture by another. It generally is applied when the subject culture is a minority culture or somehow subordinate in social, political, economic, or military status to the appropriating culture. This appropriation often occurs without any real understanding of why the original culture took part in these activities or the meanings behind these activities, often converting culturally significant artifacts, practices, and beliefs into “meaningless” pop-culture or giving them a significance that is completely different/less nuanced than they would originally have had.

Cultural appropriation is a by-product of imperialism, capitalism, oppression, and assimilation. Imperialism is the creation and maintenance of an unequal cultural, economic, and territorial relationship, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination. Imperialism functions by subordinating groups of people and territories and extracting everything of value from the colonized people and territories. In the case of cultural appropriation, culture is treated as a “natural resource” to extract from People of Colour.

Cultural appropriation is profitable. Objects and traditions (but not the people) of marginalized cultures are seen by the dominant culture as exotic, edgy, and desirable, which translates to profits.

Capitalism works best when people are not individual people with celebrated differences, but identical workers, cogs in the machine. Once diverse cultural identities are stripped away, the only culture left to identify with is capitalist culture. This is one aspect of assimilation, in which marginalized communities lose their cultural markers and are folded into the dominant culture. The process of assimilation is sped up when culture markers are appropriated by the dominant culture. Once the dominant culture has access to the cultural markers of a marginalized culture, they are no longer markers of the marginalized culture, and the marginalized culture is gobbled up by the dominant culture.

Cultural appropriation is harmful because it is an extension of centuries of racism, genocide, and oppression. Cultural appropriation treats all aspects of marginalized cultures (also known as targets of oppression) as free for the taking. It is the same rationale that has been (and still is) used to steal land and resources from People of Colour, particularly Native people.

The defence of cultural appropriation is based upon the misconception that race relations exist on a level-playing field, as though racism no longer exists. Systematic racism does still exist- white people have power and privilege in this society, while People of Colour are systematically denied power and privilege in this society.

There cannot be a truly equal and free flow of ideas, practices, and cultural markers as long as one group (white people) have power and privilege over another group (People of Colour). Spiritual practices of Native peoples are particularly prone to appropriation by the dominant culture.

It was not until the passage of the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act that Native people in the United States were legally permitted to practice their traditional spirituality. Since the colonization of this continent by white settlers, Native people have faced monumental obstacles to the free exercise of their spiritual practices, including boarding schools, 5 forced relocation, endless broken treaties, “kill the Indian, save the man” policies, and forced assimilation.

So, it is particularly insensitive for white people to attempt to justify their/our use of Native spiritual practices when Native people themselves have often been brutally persecuted for the same. Cultural appropriation is not an acceptable way to honour, respect, or appreciate People of Colour. If you wish to honour, respect, or appreciate Black people or Black culture, then you should learn how to recognize, confront, and dismantle systematic racism instead of appropriating dreadlocks, a symbol of the wearer’s commitment to Jah Rastafari and Black resistance to racism.

If you wish to honour, respect, or appreciate Native people or Native culture, learn how to listen to Native people when they identify very real problems (and how to confront them) faced by Native people today, such as astronomical suicide and alcoholism rates on reservations or the continued the! of Native lands by resource extraction companies.

Many well-intentioned and self-proclaimed antiracists will engage in cultural appropriation in the name of “solidarity.” A prominent example of this is white pro-Palestinian activists wearing Arab headscarves and symbols of Palestinian nationalism and resistance to occupation.

One must also take into account the very real climate of Islamophobia and Arab-phobia in the United States- people who are perceived as Arab and/or Muslin are treated with hostility, suspicion, and violence, and assumed to be terrorists.

Many traditions that have been appropriated from Native people (such as sweat lodges and “medicine wheel ceremonies”) are performed by white people allegedly in the name of goals like world peace, spiritual mending, and mutual understanding. One of the things needed for world peace, spiritual mending, and mutual understanding to occur is an end to racism.

But cultural appropriation is a form of racism, and as long as racism exists, there can be no world peace, spiritual mending, or mutual understanding. Many concrete steps to dismantle racism have been identified by many different people, including recognizing one’s role in perpetuating racism, confronting one’s own white privilege, and attacking the systems of oppression that give white people privilege in the first place. None of these steps require cultural appropriation.

How can you explore and take part in a culture without exploiting it for your own use?

Examine your own culture

Through self-reflection, you will be better able to understand differences and determine what is important in cultures across the world. If you realize that a specific aspect of your own cultural background is central to your identity, and it would offend you if someone were to use it without understanding fully what it means, consider that people all over the world, in cultures other than your own, may feel exactly the same way.

Think about: Would I be offended if someone wore an important religious symbol from my culture without understanding what it truly means?

Listen first: One of the best ways to understand and appreciate another culture is by listening to those who are a part of the fabric of that society. Listen to their stories, understand the implications behind the aspects of their culture that you are interested in, and use that understanding to broaden your worldview.

Think about: I recently purchased a beautiful piece of handmade jewellery. Did I listen to the artist who created the piece to learn more about his or her background, what their work means to them, and how it fits into the culture of that place? If not, I may be appropriating instead of appreciating.

Consider context: What does a certain symbol mean to a particular culture? When and where is it appropriate to use it? Understanding what the various aspects of a culture are and what they mean are so important. If you truly have an interest in a person’s life, more than likely, they will be happy to share with you the things that matter to them.

Think about: Did I just take a piece of someone’s culture to use for my own benefit, without knowing the significance behind it? Did I ask about the origins of the custom, item, or symbol? This is so important in understanding and appreciating a culture.

Share your own culture: The most important part of cultural exchange and what best distinguishes it from appropriation is that exchange is mutual. Through appreciation and exchange, you are able to share something about yourself, learn something about someone else, and partake in a mutual understanding of one another’s background and culture.

Think about: Am I equally interested in sharing a piece of my own language, food, customs, and traditions? Chances are, this person is just as excited to learn about my culture as I am about theirs. What an incredible part of cultural exchange and appreciation!

When Black culture and trends are (mis)appropriated by the white majority in these industries, the creators of that culture- Black men and women do not see profit. Or representation. Or power. This appropriation without compensation blatantly tells Black people, “Black is cool unless you’re actually Black.”

Susan Scafidi, the academic director of Fordham University’s Fashion Law Institute and a Yale Law School alum, defines cultural appropriation as taking intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expression, or artifacts from another culture without permission. The fashion industry is one of the biggest offenders when it comes to appropriation, and designers have by and large responded to criticisms and callouts with nothing more than lip service while they continue to riff off of hip hop culture and stack their runways with mostly white models.

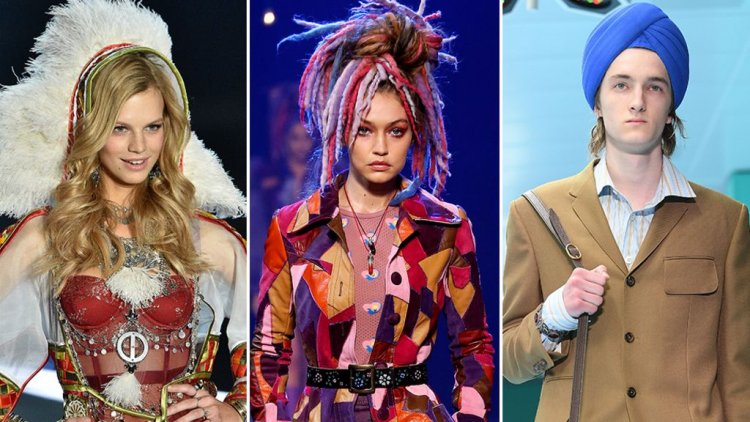

Year after year, luxury fashion brands (particularly European houses like Comme des Garcons and Valentino, as well as the American designer Marc Jacobs) send white models down the runways in Black hairstyles, only reinforcing the problem. The beauty industry is similarly guilty, rolling out “new” looks that Black people have worn for generations, the same hairstyles for which they have been discriminated against. “[Certain styles are] a result of surviving and creatively expressing a sense of resilience and pride” among Black people, says Kimberly Jenkins, founder of The Fashion and Race Database, an open-source platform working to "expand the narrative of fashion history and challenge mis-representation within the fashion system."

Take cornrows, for example. Bo Derek, a white actress and model, ironically enough popularized the style amongst a white American audience when she wore them in the 1979 film.

But history tells us that cornrows originated in Africa, and intricate braiding patterns indicated what tribe a person belonged to. It’s impossible to fully understand the history of braids without also speaking on slavery, as traffickers shaved Black women’s heads to strip them of their humanity and culture before boarding them on slave ships to America. Braiding in the U.S evolved as a secret messaging system between enslaved people to communicate maps to freedom. For a white person to wear this style, it’s purely out of vanity. The appropriation is drowned out by Instagram and Twitter "likes" that ignore and distract from the painful history that preludes today’s issues around racism and police brutality against the Black community.

But, beyond braids, Black culture has become so mainstream and synonymous with popular culture. So why, then, are some Black trends within fashion and beauty described as “ghetto” or “ratchet” when Black people wear them, but deemed “high fashion” or “trendsetting” when they’re seen on a runway or privileged person?

In 2018, model Salem Mitchell was called “ghetto” by an Instagram user when she appeared on Vogue’s Instagram page wearing box braids. When Zendaya wore dreadlocks on the 2015 Oscars red carpet to remind people of colour that their hair was good enough, then-Fashion Police host Giuliana Rancic said that Zendaya looks like she “smells like patchouli oil or weed.” But when Kylie Jenner wore faux dreadlocks for a magazine cover story, she was described as edgy, raw and beautiful.

“Suddenly everyone from all cultures seem to be fascinated with all things Black from our bodies, hair, clothes, music, and even the ghetto itself,” said Jenifer Rice-Genzuk Henry, who wrote the grown-ish episode, “Strictly 4 My…” that dialled into the many perspectives around Black appropriation. “While it’s great to be celebrated, why not celebrate Black people doing those things when they do them, and not wait for a white celebrity to conveniently and momentarily recycle those things from [Black people] for it to then become validated? It’s a direct slap in the face to the group of people who have been scrutinized, mocked, degraded and even discriminated against over the years for doing it.”

The fashion and beauty industries, along with the oft-white celebrities they employ as the faces of their brands, aren’t only feeding off Black culture for the sake of seeming “new” and “cool” and “edgy” they’re profiting from it. This goes beyond giving credit where credit is due. Black people are literally not getting paid for what they created. Meanwhile, others are reaping the monetary reward, gaining power and influence, and social cachet along the way.

Serial offenders like Kylie Jenner abuse Black culture for personal and profitable gain, like when she posted a picture wearing cornrows to draw attention to her new wig line in 2015, which resulted in activist and actress Amandla Stenberg calling her out for “cash cropping on her cornrows.” As recently as this year, Jenner wore her platinum blonde hair in twists, a protective style in the Black community that women can legally get fired for wearing in the workplace.

Many fashion brands have, in recent, weeks stated that they are against racism, but critics and Black people are screaming hypocrisy and seeing straight through those Black Lives Matter social media posts.

Take, for instance, the French luxury brand Celine, which posted a black square with a seemingly supportive caption that was quickly called out by Hollywood stylist Jason Bolden, who accused the brand of not dressing Black celebrities for the red carpet unless they were working with white stylists. It was further exposed that Black model representation for Celine’s women’s and men’s fashion shows from Spring 2019 to Fall 2020 ranged from only 6% to 12%.

Of course, there are some brands putting their money where their Instagram posts are. Glossier has donated $1 million to BLM and black-owned beauty brands; Fenty Beauty temporarily halted business in support of #BlackoutTuesday; Sephora allowed Beauty Insider members to redeem their points as donations to the National Black Justice Coalition; and Aurora James, creative director and founder of shoe brand Brother Vellies, created the 15% Pledge, which asks retailers to ensure that at least 15% of their shelf space is dedicated to Black-owned brands. (Black people account for 15% of the population in the United States.)

In 2020, cultural appropriation is no longer an issue that can be excused by offenders claiming to "not know" that sending a white model down the runway with cornrows is disrespectful. In an ideal world, this would perhaps be called an "appreciation" of culture but we don't live in that ideal world. Americans never have. So where do we go from here? Is it enough to acknowledge the contributions of Black people?

“Advocating for Black people against racism, or simply acknowledging the historical or political significance behind a trend or a statement has become trendy and performative, complicating matters even more,” said Rice-Genzuk Henry. In other words, appropriation where a non-Black person acknowledges in an Instagram caption that her hairstyle or outfit was popularized by Black culture, is still appropriation.

Some have suggested paying royalties as a means of monetary compensation. But Scafidi, the Fordham professor who also authored Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law, says, “Royalty payments to the members of a cultural group as a whole can be complicated, as they raise the question of who is part of the group and should receive them.”

“The system of intellectual property rights is designed around individual authors and inventors and not collective cultural creativity, so it is usually difficult to argue as a legal matter that a cultural group ‘owns’ its own creations, even when the ethical claim is clear,” she continues.

Culture as a whole is not an intellectual property that can be traced back to one specific person or group of people in the way that one might be able to trace a song or movie idea. Instead, culture is a mosaic of ideas and expressions that have developed over time.